Simplified JavaScript: Getting Started with Closures

October 22, 2017Eric Elliot, in his Medium article Master the JavaScript Interview: What is a Closure?, explains that when he interviews candidates for JavaScript jobs, he always asks questions about closures. He writes:

“I don’t care if a candidate knows the word “closure” or the technical definition. I want to find out if they understand the basic mechanics. If they don’t, it’s usually a clear indicator that the developer does not have a lot of experience building actual JavaScript applications.”

Elliott’s article is great if you have a pretty solid background in JS, you’ve been writing ES6 for awhile, and you’re ready to grasp the many ways JS applications use closures. This post isn’t meant to address all of those use cases. My goal is to provide you with a foundation so that you can go on to understand those other posts.

What is a closure?

There are many definitions of closures floating around the internet and most are a dense and full of jargon.

To give you a sense of these definitions, the MDN web docs describes a closure as “the combination of a function and the lexical environment within which that function was declared.”

8th Light’s description is longer, but not much clearer:

“Essentially, a closure is a structure composed of nested functions in such a way that allows us to break through the scope chain. By breaking the scope chain, closures allow access to data within inner scope that would otherwise be inaccessible by outer scope.”

Eric Elliott’s definition gets us a bit closer to understanding what a closure is, in simple terms:

"A closure is the combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function. In JavaScript, closures are created every time a function is created, at function creation time."

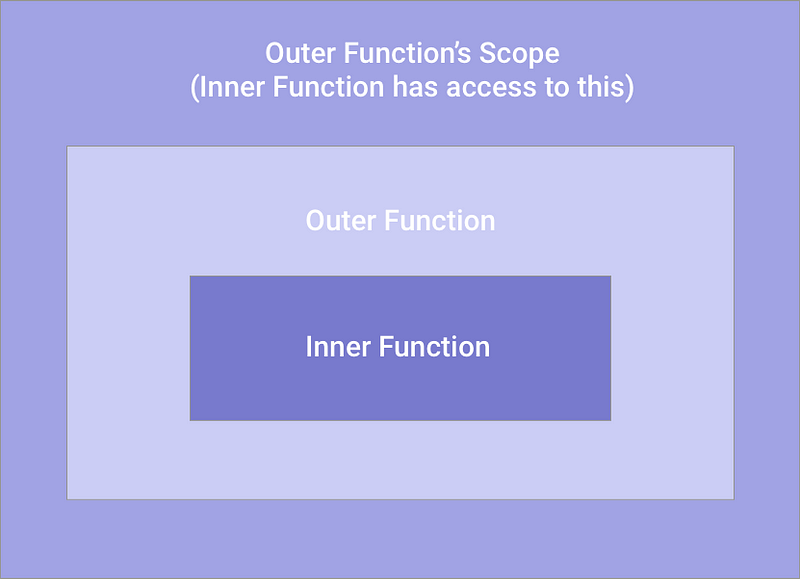

Let’s break down some of the vocabulary in this explanation to really get to the heart of what a closure is. I’ve designed a simple diagram to help us visualize what Elliott, 8th Light, and MDN are talking about.

We can start by trying to understand the meaning of lexical environment. According to Elliott, it’s a function’s “surrounding state,” or the scope available to a function.

In my diagram, the outer function’s lexical environment is represented by the outermost rectangle, which I’ve called the “Outer Function’s Scope.” The Inner Function has access to the “Outer Function’s Scope,” or “lexical environment,” thanks to the use of a closure.

In the most basic of terms, a closure is a function within another function. The inner function has access to the outer function’s scope.

How do I use a closure?

- Write a function.

- Put it inside another function.

- Expose it by returning it or passing it to another function.

Can I see an example?

There are a lot of different ways to use and write closures, but I’ll leave you with this simple example, which will springboard you into Eric Elliott’s post.

const getSum = (x, y) => { return { sum: () => x + y; }; }; getSum(1,2).sum(); // returns 3

getSum is the outer function. sum is the inner function. It is enclosed by getSum. Because sum is returned within getSum, it has access to getSum's lexical environment. sum has access to x and y, even though I have not explicitly passed x and y into sum as arguments.

And that’s about it! I hope this post has set you up to read more complicated explanations of closures, and to begin using them in your own applications.

Keep Reading

Continue Reading

I'm joining Honeycomb.io

I'm excited to share that after 3.5 years at Amplitude I'm joining Honeycomb in a little over a week.

2021: Year in Review

A review of 2021.